The spring of Seoul

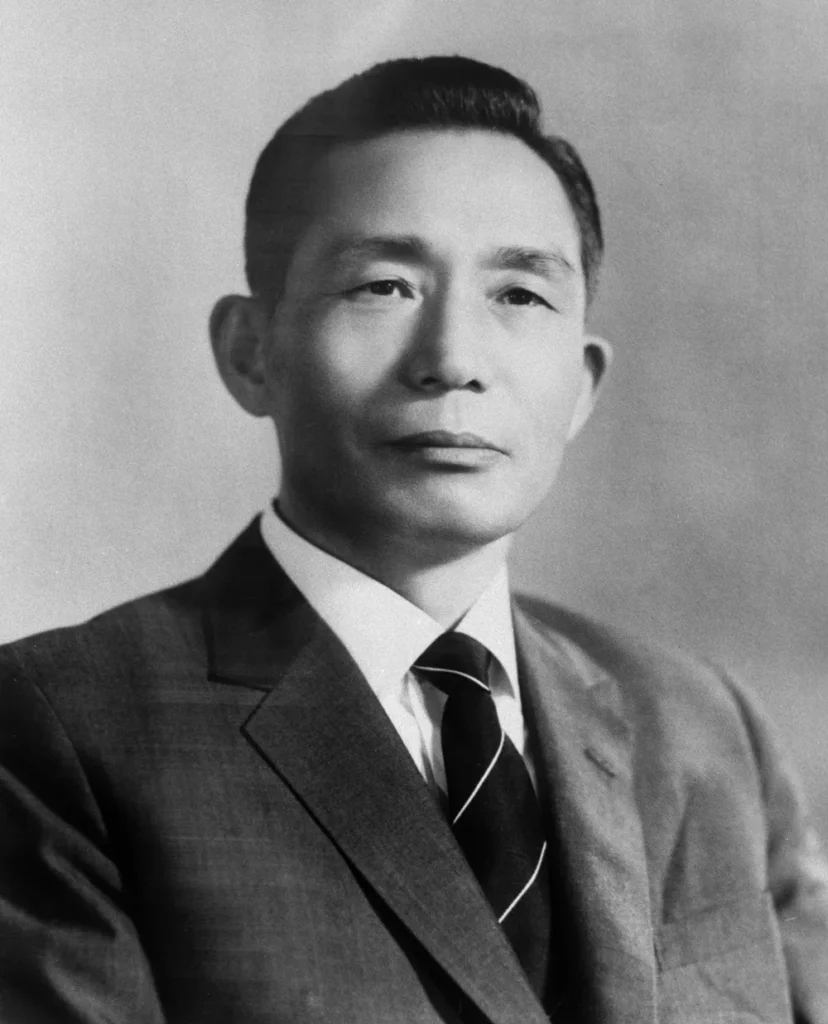

On October 26, 1979, President Park Chung-hee was assassinated by his own chief intelligence officer. This event abruptly ended Park’s authoritarian dictatorship and sparked hope among many South Koreans for the country’s democratization. This period was often called the “Spring of Seoul” during the harsh winter of 1979. However, this hope was short-lived.

On December 6, 1979, Choi Kyu-hah was elected president by a pro-government organization called the National Council for Unification, under military influence. Choi began his career as a diplomat during the Syngman Rhee regime and later cooperated with both the Rhee and Park Chung-hee authoritarian governments. The National Council for Unification, composed of pro-government figures, was the only body allowed to vote in presidential elections from 1971 to 1987.

12.12 military coup

On December 12, 1979, Colonel Chun Doo-hwan staged a military coup known as the 12.12 Military Coup. Chun, with his private faction in the military called Hanahoe (Group of One), seized control of the Korean army and reduced President Choi Kyu-hah to a mere puppet. Hanahoe had gained Park Chung-hee’s trust and wielded significant influence within the South Korean military.

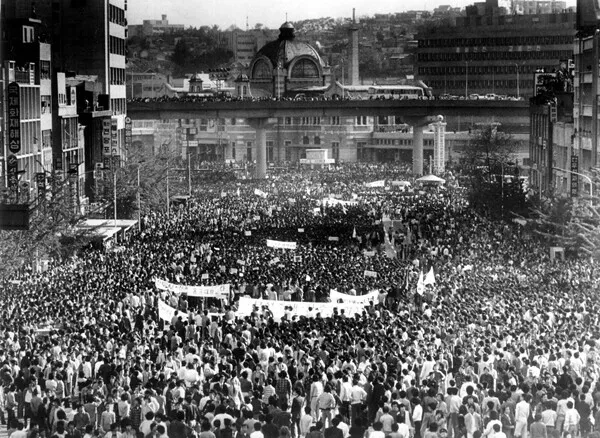

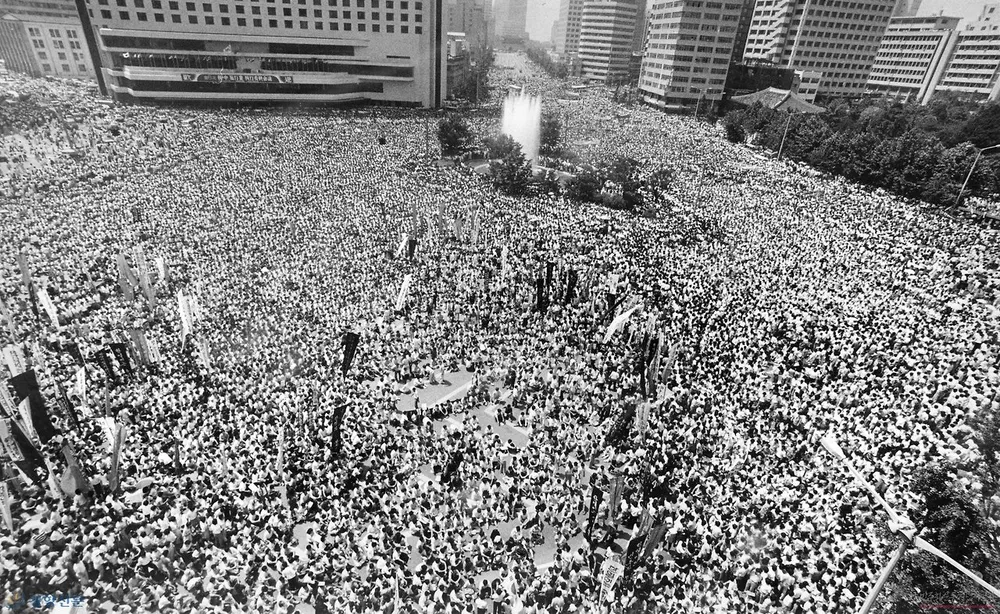

Despite this, many South Koreans opposed military dictatorship and demanded democratization. Workers and university students organized large-scale protests against Chun Doo-hwan’s regime. On May 14, 1980, around 70,000 protesters gathered in front of the Seoul City Council and Seoul Station, calling for the resignation of military authorities. Although the demonstration was dispersed to ensure the protesters’ safety, it heightened the military regime’s sense of crisis. In response, Chun Doo-hwan declared martial law nationwide, banning political activities and controlling the press. This martial law became the immediate trigger for the Gwangju Uprising.

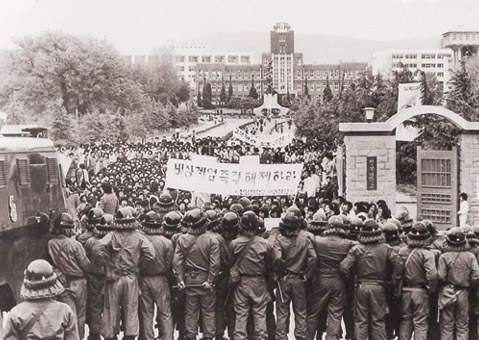

“End martial law!”, “Restore democracy!”

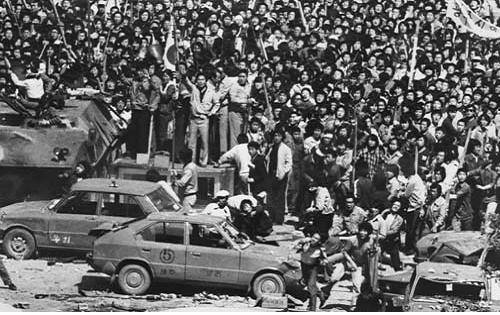

On May 18, 1980, students from Chonnam National University initiated a protest against the violent enforcement of martial law. They informed citizens about the regime’s illegal actions and encouraged broader participation. Citizens demanding democratization gathered in front of the South Jeolla Provincial Government building. Martial law troops arrested protesters and used brutal force. Some protesters were tortured. Those incidents fueling public outrage and drawing more people into the demonstrations.

Bus and taxi drivers blocked the movement of soldiers, while citizens shouted “End martial law!” and “Restore democracy!” Injured individuals were helped by others, but the mainstream media largely concealed the truth. Gwangju MBC’s biased reporting only heightened citizens’ anger, which ignited like wildfire.

Resistance of Gwangju Citizens

On May 21, martial law troops opened fire on civilians. The first death in front of Gwangju Station marked the beginning of indiscriminate killings across the city. Dead bodies were strewn on the streets. Citizens fought back by throwing Molotov cocktails, though this resistance had its limits. That day, fifty citizens, including a pregnant woman, were killed by martial law troops. Nevertheless, the uprising spread throughout the entire Jeonnam province.

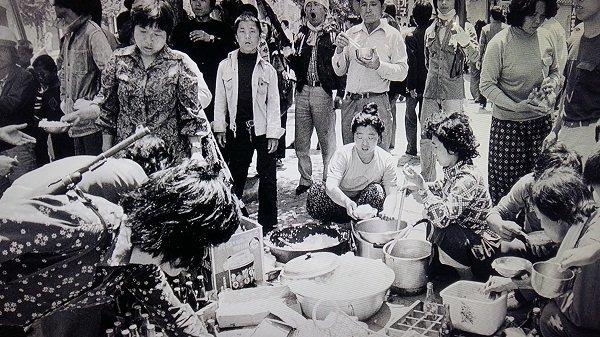

Armed resistance grew stronger as citizens seized weapons from police stations and formed a militia. This self-governing citizen militia established new social order and values. Citizens supported the militia by cooking rice balls and donating supplies for the injured. However, their efforts remained unstable due to continuous attacks from martial law troops. The government and media suppressed the truth about the uprising, labeling the citizens as rioters. The massacre continued. On May 24, in Junam Village, eleven out of twelve bus passengers were killed by soldiers’ gunfire.

The government and media suppressed the truth about the uprising, labeling the citizens as rioters. The massacre continued. On May 24, in Junam Village, eleven out of twelve bus passengers were killed by soldiers’ gunfire. Between May 21 and 27, a total of 165 people were killed, 76 went missing, and 3,516 were injured in Gwangju. Despite risking their lives, the citizens could not withstand the overwhelming firepower of the martial law troops. On May 27, Gwangju fell to the martial law troops. Following the uprising, Chun Doo-hwan, the orchestrator of the massacre, became president.

Armed resistance grew stronger as citizens seized weapons from police stations and formed a militia. This self-governing citizen militia established new social order and values. Citizens supported the militia by cooking rice balls and donating supplies for the injured. However, their efforts remained unstable due to continuous attacks from martial law troops. Despite government repression, the spirit of the Gwangju May 18 Uprising did not fade. By the mid-1980s, the truth about Gwangju spread widely across universities, where students commemorated the uprising and organized anti-dictatorship demonstrations.

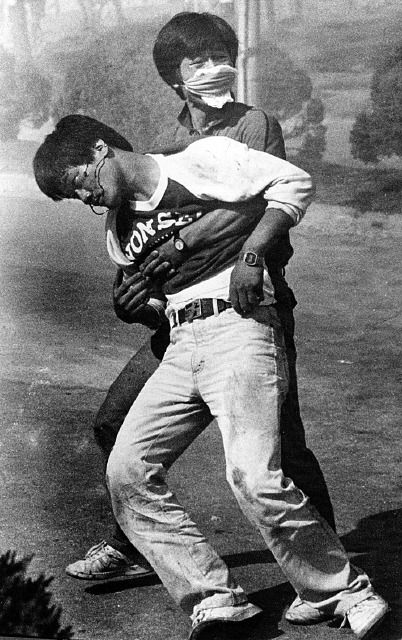

by a tear gas canister.

In June 1987, the Chun Doo-hwan regime tortured university student Park Jong-chul to death by waterboarding because of his participation in pro-democracy protests. Shortly afterward, another student activist, Lee Han-yeol, died after being hit by a tear gas canister during a demonstration. These two incidents ignited nationwide outrage against Chun’s dictatorship.

Even white-collar workers, known as the “Necktie Brigade,” joined the protests, forcing the military government to promise constitutional reforms, including direct presidential elections. This wave of protests is known as the June Democracy Movement. The June Democracy Movement was born out of the Gwangju uprising. The hope of the people of Gwangju was finally realized in this movement, making it one of the greatest chapters in South Korea’s democratic history.

Han Kang, winner of the Nobel Literary Award, said that while writing a novel about the May 18th movement, there were moments when she felt, “the past was helping the present, and the dead were saving the living.” As she described, the Gwangju uprising deeply affected South Korean society. The peaceful impeachment of former Presidents Park Geun-hye and Yoon Suk-yeol is also a testament to the enduring spirit of the May 18 movement influencing the present day.